Médan magnétik

| Éléktromagnétisme | ||

|---|---|---|

| Listrik · Magnétisme | ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

Dina fisika, médan magnétik nyaéta hiji médan anu nembus rohangan sarta ngeprakkeun gaya magnétik kana muatan listrik jeung batang magnétik dua kutub. Médan magnétik ngurilingan arus listrik, batang magnét dua kutub, sarta médan listrik anu barobah.

Mangsa ditempatkeun dina hiji medan magnétik, batang magnétik ngalempengkeun sumbuna supaya sajajar jeung médan magnétik, saperti bisa kasaksén lamun bubuk beusi aya di sabudeureun hiji magnét (tempo gambar di beulah kénca). Médan magnétik ogé boga énergi jeung moméntum sorangan, kalayan rapat énergina sabanding jeung kuadrat tina inténsitas médan. Médan magnétik diukur maké hijian teslas (hijian SI) atawa gauss (hijian cgs).

Aya sababaraha sifat médan magnétik anu katempo. Pikeun fisika nu ngabahas bahan magnétik, tempo magnétisme jeung magnét, sarta pikeun leuwih jero tempo ferromagnétisme, paramagnétisme, jeung diamagnétisme. Pikeun médan magnét nu tetep, saperti anu dihasilkeun ku batang magnétik dua kutub anu stasionér jeung arus anu tetep, tempo magnétostatika. Pikeun médan magnétik anu dihasilkeun ku médan listrik anu barobah, tempo éléktromagnétisme.

Médan listrik jeung médan magnét mangrupa unsur-unsur anu ngawangun médan éléktromagnétik.

|

|

Artikel ieu keur dikeureuyeuh, ditarjamahkeun tina basa Inggris. Bantuanna didagoan pikeun narjamahkeun. |

Définisi

[édit | édit sumber]In classical physics,the magnetic field is a vector field (that is, some vector at every point of space and time), with SI units of teslas (one tesla is one newton-second per coulomb-metre) and cgs units of gauss. It has the property of being a solenoidal vector field.

The field can be both defined and méasured by méans of a small magnetic dipole (i.e., bar magnet). The magnetic field exerts a torque on magnetic dipoles that tends to maké them point in the same direction as the magnetic field (as in a compass), and moréover the magnitude of that torque is proportional to the magnitude of the magnetic field. Therefore, in order to méasure the magnetic field at a particular point in space, you can put a small freely-rotating bar magnet (such as a compass) there: the direction it winds up pointing is the direction of ; and the ratio of the maximum magnitude of the torque to the dipole moment of the bar magnet is the magnitude .

(There are, in addition, several other different but physically equivalent ways to define the magnetic field, for example via the Lorentz force law (see below), or as the solution to Maxwell's equations.)

It follows from any of these definitions that the magnetic field vector (being a vector product) is a pseudovector (also called an axial vector).

B jeung H

[édit | édit sumber]There are two quantities that physicists may refer to as the magnetic field, notated and . The vector field is known among electrical engineers as the magnetic field intensity or magnetic field strength also known as auxiliary magnetic field or magnetizing field. The vector field is known as magnetic flux density or magnetic induction or simply magnetic field, as used by physicists, and has the SI units of teslas (T), equivalent to webers (Wb) per square metre or volt seconds per square metre. Magnetic flux has the SI units of webers so the field is that of its aréal density. [1][2][3] Archived 2008-09-05 di Wayback Machine[4][1] The vector field has the SI units of amperes per metre and is something of the magnetic analog to the electric displacement field represented by , with the SI units of the latter being ampere-seconds per square metre. Although the term "magnetic field" was historically reserved for , with being termed the "magnetic induction", is now understood to be the more fundamental entity, and most modérn writers refer to as the magnetic field, except when context fails to maké it cléar whether the quantity being discussed is or . See:[2]

The difference between the and the vectors can be traced back to Maxwell's 1855 paper entitled On Faraday's Lines of Force. It is later clarified in his concept of a séa of molecular vortices that appéars in his 1861 paper On Physical Lines of Force - 1861. Within that context, represented pure vorticity (spin), wheréas was a weighted vorticity that was weighted for the density of the vortex séa. Maxwell considered magnetic permeability µ to be a méasure of the density of the vortex séa. Hence the relationship,

(1) Magnetic induction current causes a magnetic current density

was essentially a rotational analogy to the linéar electric current relationship,

(2) Electric convection current

where is electric charge density. was seen as a kind of magnetic current of vortices aligned in their axial planes, with being the circumferential velocity of the vortices. With µ representing vortex density, we can now see how the product of µ with vorticity léads to the term magnetic flux density which we denote as .

The electric current equation can be viewed as a convective current of electric charge that involves linéar motion. By analogy, the magnetic equation is an inductive current involving spin. There is no linéar motion in the inductive current along the direction of the vector. The magnetic inductive current represents lines of force. In particular, it represents lines of inverse square law force.

The extension of the above considerations confirms that where is to , and where is to ρ, then it necessarily follows from Gauss's law and from the equation of continuity of charge that is to . Ie. parallels with , wheréas parallels with .

In SI units, and are méasured in teslas (T) and amperes per metre (A/m), respectively; or, in cgs units, in gauss (G) and oersteds (Oe), respectively. Two parallel wires carrying an electric current in the same direction will generate a magnetic field that will cause a force of attraction between them. This fact is used to define the value of an ampere of electric current.

The fields and are also related by the equation

where is magnetization.

Gaya akibat médan magnétik

[édit | édit sumber]Gaya kana partikel anu dibere muatan

[édit | édit sumber]

where

- F is the force (in newtons)

- q is the electric charge of the particle (in coulombs)

- v is the instantaneous velocity of the particle (in metres per second)

- B is the magnetic field (in teslas)

- and × is the cross product.

Gaya kana kawat nu arusna barobah

[édit | édit sumber]A straight, stationary wire carrying an electric current, when placed in an external magnetic field, feels a force. This force is the result of the Lorentz force (see above) acting on éach electron (or any other charge carrier) moving in the wire. The formula for the total force is as follows:

where

- F = Force, measured in newtons

- I = current in wire, measured in amperes

- B = magnetic field vector, measured in teslas

- = vector cross product

- L = a vector, whose magnitude is the length of wire (measured in metres), and whose direction is along the wire, aligned with the direction of conventional current flow.

Alternatively, some authors write

where the vector direction is now associated with the current variable, instéad of the length variable. The two forms are equivalent.

If the wire is not straight but curved, the force on it can be computed by applying this formula to éach infinitesimal segment of wire, then adding up all these forces via integration.

The Lorentz force on a macroscopic current is often referred to as the Laplace force.

Arah gaya

[édit | édit sumber]

The direction of force is determined by the above equations, in particular using the right-hand rule to evaluate the cross product. Equivalently, one can use Fleming's left hand rule for motion, current and polarity to determine the direction of any one of those from the other two, as seen in the example. It can also be remembéréd in the following way. The digits from the thumb to second finger indicate 'Force', 'B-field', and 'I(Current)' respectively, or F-B-I in short. Another similar trick is the right hand grip rule.

Médan magnétik tina arus tetep

[édit | édit sumber]

The magnetic field generated by a steady current (a continual flow of charges, for example through a wire, which is constant in time and in which charge is neither building up nor depleting at any point), is described by the Biot-Savart law:

(in SI units), where

- is the current,

- is a vector, whose magnitude is the length of the differential element of the wire, and whose direction is the direction of conventional current,

- is the differential contribution to the magnetic field resulting from this differential element of wire,

- is the magnetic constant,

- is the unit displacement vector from the wire element to the point at which the field is being computed, and

- is the distance from the wire element to the point at which the field is being computed.

This is a consequence of Ampere's law, one of the four Maxwell's equations. Alternatively, it can be thought of as a true, empirical law in its own right, which contributes to the derivation of Maxwell's equations. From a practical point of view, though, the law is true and useful regardless of its philosophical origin.

Pasifatan

[édit | édit sumber]Garis médan magnétik

[édit | édit sumber]Like any vector field, the magnetic field can be depicted with field lines—a set of lines through space whose direction at any point is the direction of the local magnetic field vector, and whose density is proportional to the magnitude of the local magnetic field vector. Note that the choice of which field lines to draw in such a depiction is arbitrary, apart from the requirement that they be spaced out so that their density approximates the magnitude of the local field. The level of detail at which the magnetic field is depicted can be incréased by incréasing the number of lines.

Although any vector field can be depicted with field lines, this visualization is particularly helpful for the magnetic field (in three-dimensional space), as it makes certain aspects of it more transparent. For example, "Gauss's law for magnetism" states that the magnetic field is solenoidal (has zero divergence). This is equivalent to the simple statement that, in any field-line depiction of a magnetic field, the field lines cannot have starting or ending points; they must form a closed loop, or else extend to infinity on both ends.

Various physical phenomena have the effect of displaying field lines. For example, iron filings placed in a magnetic field will line up in such a way as to visually show magnetic field lines (see figure at top); although a close inspection will revéal that the "lines" are not quite continuous. Another place where magnetic field lines are visually displayed is in the polar auroras, in which visible stréaks of light line up with the local direction of éarth's magnetic field (due to plasma particle dipole interactions).

Note that when a magnetic field is depicted with field lines, it is not méant to imply that the field is only nonzero along the drawn-in field lines. The field is typically smooth and continuous everywhere, and can be estimated at any point (whether on a field line or not) by looking at the direction and density of the field lines néarby. The use of iron filings to display a field presents something of an exception to this picture: the magnetic field is in fact much larger along the "lines" of iron, due to the large permeability of iron relative to air.

The direction of the magnetic field corresponds to the direction that a magnetic dipole (such as a small magnet) will orient itself in that magnetic field (see definition above). Therefore, a cluster of small particles of ferromagnetic material, such as iron filings, placed in the magnetic field will line up in such a way as to visually show the magnetic field lines (see figure at top). Another place where magnetic field lines are visually displayed is the polar auroras, in which visible stréaks of light line up with the local direction of éarth's magnetic field.

Kabingung dina nandaan kutub

[édit | édit sumber]See also North Magnetic Pole and South Magnetic Pole.

The end of a compass needle that points north was historically called the "north" magnetic pole of the needle. Since dipoles are vectors and align "head to tail" with éach other to minimize their magnetic potential energy, the magnetic pole located néar the géographic North Pole is actually the "south" pole.

The "north" and "south" poles of a magnet or a magnetic dipole are labelled similarly to north and south poles of a compass needle. Néar the north pole of a bar or a cylinder magnet, the magnetic field vector is directed out of the magnet; néar the south pole, into the magnet. This magnetic field continues inside the magnet (so there are no actual "poles" anywhere inside or outside of a magnet where the field stops or starts). Bréaking a magnet in half does not separate the poles but produces two magnets with two poles éach.

Earth's magnetic field is probably produced by electric currents in its liquid core.

Médan magnétik anu muter

[édit | édit sumber]The rotating magnetic field is a key principle in the operation of alternating-current motors. A permanent magnet in such a field will rotate so as to maintain its alignment with the external field. This effect was conceptualized by Nikola Tesla, and later utilised in his, and others, éarly AC (alternating-current) electric motors. A rotating magnetic field can be constructed using two orthogonal coils with 90 degrees phase difference in their AC currents. However, in practice such a system would be supplied through a three-wire arrangement with unequal currents. This inequality would cause serious problems in standardization of the conductor size and so, in order to overcome it, three-phase systems are used where the three currents are equal in magnitude and have 120 degrees phase difference. Three similar coils having mutual géometrical angles of 120 degrees will créate the rotating magnetic field in this case. The ability of the three-phase system to créate a rotating field, utilized in electric motors, is one of the main réasons why three-phase systems dominate the world's electrical power supply systems.

Because magnets degrade with time, synchronous motors and induction motors use short-circuited rotors (instéad of a magnet) following the rotating magnetic field of a multicoiled stator. The short-circuited turns of the rotor develop eddy currents in the rotating field of the stator, and these currents in turn move the rotor by the Lorentz force.

In 1882, Nikola Tesla identified the concept of the rotating magnetic field. In 1885, Galileo Ferraris independently reséarched the concept. In 1888, Tesla gained U.S. Patent 381968 for his work. Also in 1888, Ferraris published his reséarch in a paper to the Royal Academy of Sciences in Turin.

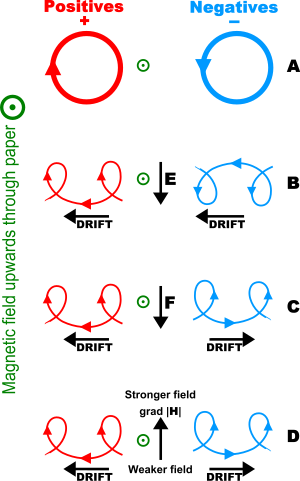

Éfék Hall

[édit | édit sumber]Because the Lorentz force is charge-sign-dependent (see above), it results in charge separation when a conductor with current is placed in a transverse magnetic field, with a buildup of opposite charges on two opposite sides of conductor in the direction normal to the magnetic field, and the potential difference between these sides can be méasured.

The Hall effect is often used to méasure the magnitude of a magnetic field as well as to find the sign of the dominant charge carriers in semiconductors (negative electrons or positive holes).

Rélativitas husus jeung éléktromagnétisme

[édit | édit sumber]According to special relativity, electric and magnetic forces are part of a single physical phenomenon, electromagnetism; an electric force perceived by one observer will be perceived by another observer in a different frame of reference as a mixture of electric and magnetic forces. A magnetic force can be considered as simply the relativistic part of an electric force when the latter is seen by a moving observer.

More specifically, rather than tréating the electric and magnetic fields as separate fields, special relativity shows that they naturally mix together into a rank-2 tensor, called the electromagnetic tensor. This is analogous to the way that special relativity "mixes" space and time into spacetime, and mass, momentum and energy into four-momentum.

Gambaran wangunan médan magnétik

[édit | édit sumber]

- An azimuthal magnetic field is one that runs éast-west.

- A meridional magnetic field is one that runs north-south. In the solar dynamo modél of the Sun, differential rotation of the solar plasma causes the meridional magnetic field to stretch into an azimuthal magnetic field, a process called the omega-effect. The reverse process is called the alpha-effect.[3]

- A dipole magnetic field is one seen around a bar magnet or around a particle with nonzero spin.

- A quadrupole magnetic field is one seen, for example, between the poles of four bar magnets. The field strength grows linéarly with the radial distance from its longitudinal axis.

- A solenoidal magnetic field is similar to a dipole magnetic field, except that a solid bar magnet is replaced by a hollow electromagnetic coil magnet.

- A toroidal magnetic field occurs in a doughnut-shaped coil, the electric current spiraling around the tube-like surface, and is found, for example, in a tokamak.

- A poloidal magnetic field is generated by a current flowing in a ring, and is found, for example, in a tokamak.

Tempo ogé

[édit | édit sumber]General

- Electric field — effect produced by an electric charge that exerts a force on charged objects in its vicinity.

- Electromagnetic field — a field composed of two related vector fields, the electric field and the magnetic field.

- Electromagnetism — the physics of the electromagnetic field: a field, encompassing all of space, composed of the electric field and the magnetic field.

- Magnetism — phenomenon by which materials exert an attractive or repulsive force on other materials.

- Magnetohydrodynamics — the academic discipline which studies the dynamics of electrically conducting fluids.

- Magnetic flux

- Magnetic monopole — hypothetical physical quantity which would cause nonzero divergence of magnetic field.

- Magnetic reconnection - an effect which causes solar flares and auroras.

- SI electromagnetism units

Mathematics

- Ampére's law — magnetic equivalent of Gauss's law.

- Biot-Savart law — the magnetic field set up by a stéadily flowing line current.

- Magnetic helicity — extent to which a magnetic field "wraps around itself".

- Maxwell's equations — four equations describing the behavior of the electric and magnetic fields, and their interaction with matter.

Applications

- Helmholtz coil — a device for producing a region of néarly uniform magnetic field.

- Maxwell coil — a device for producing a large volume of almost constant magnetic field.

- Earth's magnetic field — a discussion of the magnetic field of the éarth.

- Dynamo theory — a proposed mechanism for the création of the éarth's magnetic field.

- Electric motor — AC motors used magnetic fields.

- Rapid-decay theory - a créationist théory.

- Stellar magnetic field — a discussion of the magnetic field of stars.

- Teltron Tube

Rujukan

[édit | édit sumber]Web

- Keitch, Paul, Magnetic Field Strength and Magnetic Flux Density, diakses tanggal 2007-06-04

- Oppelt, Arnulf (2006-11-02), magnetic field strength, diakses tanggal 2007-06-04 Archived 2008-09-05 di Wayback Machine

- magnetic field strength converter, diakses tanggal 2007-06-04

Buku

- Durney, Carl H. and Johnson, Curtis C. (1969). Introduction to modern electromagnetics. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-018388-0.

- Rao, Nannapaneni N. (1994). Elements of engineering electromagnetics (4th ed.). Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-13-948746-8.

- Griffiths, David J. (1999). Introduction to Electrodynamics (3rd ed.). Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-13-805326-X.

- Jackson, John D. (1999). Classical Electrodynamics (3rd ed.). Wiley. ISBN 0-471-30932-X.

- Tipler, Paul (2004). Physics for Scientists and Engineers: Electricity, Magnetism, Light, and Elementary Modern Physics (5th ed.). W. H. Freeman. ISBN 0-7167-0810-8.

- Furlani, Edward P. (2001). Permanent Magnet and Electromechanical Devices: Materials, Analysis and Applications. Academic Press Series in Electromagnetism. ISBN 0-12-269951-3.

Cutatan

[édit | édit sumber]- ↑ Magnetic Field Strength is also sometimes called Magnetic Field Intensity. For more information reference the sources Durney and Johnson, and also Rao.

- ↑ The standard graduate textbook by Jackson follows this usage. Edward Purcell, in Electricity and Magnetism, McGraw-Hill, 1963, writes, Even some modern writers who treat B as the primary field feel obliged to call it the magnetic induction because the name magnetic field was historically preempted by H. This seems clumsy and pedantic. If you go into the laboratory and ask a physicist what causes the pion trajectories in his bubble chamber to curve, he'll probably answer "magnetic field," not "magnetic induction." You will seldom hear a geophysicist refer to the earth's magnetic induction, or an astrophysicist talk about the magnetic induction of the galaxy. We propose to keep on calling B the magnetic field. As for H, although other names have been invented for it, we shall call it "the field H" or even "the magnetic field H".

- ↑ The Solar Dynamo, retrieved Sep 15, 2007.

Tumbu luar

[édit | édit sumber]Information

- Crowell, B., "Electromagnetism Archived 2011-06-03 di Wayback Machine".

- Nave, R., "Magnetic Field". HyperPhysics.

- "Magnetism", The Magnetic Field Archived 2006-07-09 di Wayback Machine. théory.uwinnipeg.ca.

- Hoadley, Rick, "What do magnetic fields look like Archived 2011-02-19 di Wayback Machine?" 17 July 2005.

Field density

- Jiles, David (1994). Introduction to Electronic Properties of Materials (1st ed.). Springer. ISBN 0-412-49580-5.

Rotating magnetic fields

- "Rotating magnetic fields". Integrated Publishing.

- "Introduction to Generators and Motors", rotating magnetic field. Integrated Publishing.

- "Induction Motor-Rotating Fields Archived 2005-09-29 di Wayback Machine".

Diagrams

- McCulloch, Malcolm,"A2: Electrical Power and Machines", Rotating magnetic field Archived 2006-04-27 di Wayback Machine. eng.ox.ac.uk.

- "AC Motor Theory" Figure 2 Rotating Magnetic Field. Integrated Publishing.

Journal Articles

- Yaakov Kraftmakher, "Two experiments with rotating magnetic field". 2001 Eur. J. Phys. 22 477-482.

- Bogdan Mielnik and David J. Fernández C., "An electron trapped in a rotating magnetic field". Journal of Mathematical Physics, February 1989, Volume 30, Issue 2, pp. 537–549.

- Sonia Melle, Miguel A. Rubio and Gerald G. Fuller "Structure and dynamics of magnetorheological fluids in rotating magnetic fields". Phys. Rev. E 61, 4111 – 4117 (2000).