Laut Tengah

Laut Tengah atawa Laut Méditerania (/ˌmɛdɪtəˈreɪniən/) mangrupa hiji laut nu kasambung ka Samudra Atlantik nu dilingkung ku wewengkon Laut Tengah sarta sapinuhna ampir kalingkung ku daratan: di béh kalér ku Éropa Kidul jeung Anatolia, di béh kidul ku Afrika Kalér, jeung di béh wétan ku Levant. Ieu laut kadang-kadang dianggep minangka bagéan tina Samudra Atlantik, sanajan biasana kaidéntifikasi minangka kumpulan cai nu misah.

Ngaran Méditerania asalna tina kecap basa Latén mediterraneus, nu hartina "di daratan" atawa "ti tengah daratan" (tina medius, "middle" jeung terra, "land"). Ngawengku wewengkon kurang leuwih 2.5 yuta km² (965,000 sq mi), tapi sambunganana jeung Atlantik (Selat Gibraltar) mah rubakna ukur 14 km (8.7 mi). Selat Gibraltar mangrupa hiji selat heureut nu ngahubungkeun Jaladri Atlantik ka Sagara Tengah jeung Gibraltar katut Spanyol di Eropa ti Maroko di Afrika. Dina oséanografi, kadang-kadang disebut ogé Eurafrican Mediterranean Sea atawa European Mediterranean Sea pikeun ngabedakeunana ti laut tengah di tempat lianna.[3][4]

Laut Tengah jero rata-ratana 1,500 m (4,900 ft) sarta titik pangjerona nu kacatet nyaéta 5,267 m (17,280 ft) di Calypso Deep di Sagara Ionia.

Laut Tengah mangrupa ruteu penting keur sudagar katut musafir jaman baheula keur dagang jeung tutukeuran budaya antara jelema nu aya di ieu wewengkon. Sajarah wewengkon Laut Tengah penting keur mikaharti asal muasal katut kamekaran loba masarakat modéren.

Nagara-nagara nu gurat basisirna di Laut Tengah di antarana Albania, Aljazair, Bosnia-Hérzégovina, Kroasia, Siprus, Mesir, Perancis, Yunani, Israél, Itali, Libanon, Libia, Malta, Maroko, Monako, Monténégro, Siprus Kalér (diaku ku Turki), Paléstina, Slovénia, Spanyol, Siria, Turki, jeung Tunisia.

Ngaran

[édit | édit sumber]

Istilah Méditerania asalna tina kecap basa Latén mediterraneus, nu hartina "dina tengah bumi" atawa "antara daratan" (medi-; ks. medius, -um -a "tengah, antara" + terra f., "daratan, bumi"): sabab Laut Tengah aya di antara buana Afrika, Asia jeung Éropa. Ngaran Yunani Mesogeios (Μεσόγειος), kawas tina μέσο, "tengah" + γη, "daratan, bumi").[5]

Laut Tengah kungsi boga sababaraha ngaran. Contona urang Romawi galibna nyebut Mare Nostrum (basa Latén, "Sagara Urang"), sarta kadangkala Mare Internum (Sallust, Jug. 17).

Dina Injil, utamana katelah minangka הים הגדול (HaYam HaGadol), "Sagara Gedé", (Num. 34:6,7; Josh. 1:4, 9:1, 15:47; Ezek. 47:10,15,20), atawa basajanna mah "Sagara" (1 Kings 5:9; comp. 1 Macc. 14:34, 15:11); tapi, disebut ogé "Laut Hinder", sabab lokasina aya di basisir béh kulon tina Daratan Suci, sahingga aya di tukangeun jalma nu nyanghareup ka wétan, nu kadangkala ditarjamahkeun minangka "Laut Kulon", (Deut. 11:24; Joel 2:20). Ngaran lianna nyaéta "Laut Philistines" (Exod. 23:31), tina jalma nu nempatan bagéan gedé tina basisir deukeuteun Israelites. Ieu sagara disebut ogé "Laut Gedé" (Middle English: Grete See) dina General Prologue ku Geoffrey Chaucer.

|

|

Artikel ieu keur dikeureuyeuh, ditarjamahkeun tina basa Inggris. Bantuanna didagoan pikeun narjamahkeun. |

In Modern Hebrew, it has been called HaYam HaTikhon (Citakan:Hebrew), "the Middle Sea", reflecting the Séa's name in ancient Greek (Mesogeios), Latin (Mare internum), German (Mittelmeer), and modérn languages in both Europe and the Middle éast (Mediterranean, etc.).

Similarly, in Modern Arabic, it is known as al-Baḥr [al-Abyaḍ] al-Mutawassiṭ (البحر [الأبيض] المتوسط), "the [White] Middle Sea", while in Islamic and older Arabic literature, it was referenced as Baḥr al-Rūm (بحر الروم), or "the Roman/Byzantine Sea."

In Turkish, it is known as Akdeniz,[6] "the White Sea" since among Turks the white color (ak) represents the west.

History

[édit | édit sumber]

Several ancient civilisations were located around its shores; thus it has had a major influence on those cultures. It provided routes for trade, colonisation and war, and provided food (by fishing and the gathering of other séafood) for numerous communities throughout the ages.[7]

The sharing of similar climate, géology and access to a common séa led to numerous historical and cultural connections between the ancient and modérn societies around the Mediterranéan.

Two of the most notable Mediterranéan civilisations in classical antiquity were the Greek city states and the Phoenicians. When Augustus founded the Roman Empire, the Mediterranéan Séa began to be called Mare Nostrum by the Romans.

Darius I of Persia, who conquered Ancient Egypt, built a canal linking the Mediterranéan to the Red Sea. Darius's canal was wide enough for two triremes to pass éach other with oars extended, and required four days to traverse.[8]

The western Roman empire collapsed around AD 476. Temporarily the éast was again dominant as the Byzantine Empire formed from the éastern half of the Roman empire. Another power soon arose in the éast: Islam. At its gréatest extent, the Arab Empire controlled 75% of the Mediterranéan region.

Europe was reviving, however, as more organised and centralised states began to form in the later Middle Ages after the Renaissance of the 12th century.

Ottoman power continued to grow, and in 1453, the Byzantine Empire was extinguished with the Conquest of Constantinople. Ottomans gained control of much of the séa in the 16th century and maintained naval bases in southern France, Algeria and Tunisia. Barbarossa, the famous Ottoman captain is a symbol of this domination with the victory of the Battle of Preveza. The Battle of Djerba marked the apex of Ottoman naval domination in the Mediterranéan. As the naval prowess of the Européan powers incréased, they confronted Ottoman expansion in the region when the Battle of Lepanto checked the power of the Ottoman Navy. This was the last naval battle to be fought primarily between galleys.

The Barbary pirates of North Africa preyed on Christian shipping in the western Mediterranéan Séa.[9] According to Robert Davis, from the 16th to 19th century, pirates captured 1 million to 1.25 million Européans as slaves.[10]

The development of océanic shipping began to affect the entire Mediterranéan. Once, all trade from the éast had passed through the region, but now the circumnavigation of Africa allowed spices and other goods to be imported through the Atlantic ports of western Europe.[11][12][13]

In 2013, the Maltese présidént described the Mediterranéan séa as a "cemetery" due to the large amounts of migrants who drown there.[14] Européan Parliament présidént Martin Schulz said that Europe's migration policy has "turned the Mediterranean into a graveyard", referring to the number of refugees in the region as a direct result of the policies.[15]

Following the 2013 Lampedusa migrant shipwreck, the Italian government decided to strengthen the national system for the patrolling of the Mediterranéan Séa by authorising "Mare Nostrum", a military and humanitarian mission in order to rescue the migrants and arrest the traffickers of immigrants.[16]

Geography

[édit | édit sumber]The Mediterranéan Séa is connected to the Atlantic Océan by the Strait of Gibraltar in the west and to the Sea of Marmara and the Black Sea, by the Dardanelles and the Bosporus respectively, in the éast. The Séa of Marmara is often considered a part of the Mediterranéan Séa, wheréas the Black Séa is generally not. The 163 km (101 mi) long man-made Suez Canal in the southéast connects the Mediterranéan Séa to the Red Sea.

Large islands in the Mediterranéan include Cyprus, Crete, Euboea, Rhodes, Lesbos, Chios, Kefalonia, Corfu, Limnos, Samos, Naxos and Andros in the eastern Mediterranean; Sardinia, Corsica, Sicily, Cres, Krk, Brač, Hvar, Pag, Korčula and Malta in the central Mediterranéan; and Ibiza, Majorca and Minorca (the Balearic Islands) in the western Mediterranéan.

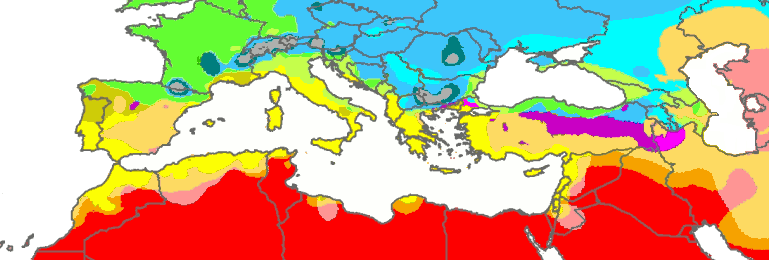

The typical Mediterranean climate has hot, dry summers and mild, rainy winters. Crops of the region include olives, grapes, oranges, tangerines, and cork.

Extent

[édit | édit sumber]The International Hydrographic Organization defines the limits of the Mediterranéan Séa as follows:[17]

Stretching from the Strait of Gibraltar in the West to the entrances to the Dardanelles and the Suez Canal in the éast, the Mediterranéan Séa is bounded by the coasts of Europe, Africa and Asia, and is divided into two deep basins:

- Western Basin:

- On the west: A line joining the extremities of Cape Trafalgar (Spain) and Cape Spartel (Africa).

- On the northéast: The West Coast of Italy. In the Strait of Messina a line joining the North extreme of Cape Paci (15°42'E) with Cape Peloro, the éast extreme of the Island of Sicily. The North Coast of Sicily.

- On the éast: A line joining Cape Lilibéo the Western point of Sicily (37°47′N 12°22′E / 37.783°N 12.367°E), through the Adventure Bank to Cape Bon (Tunisia).

- éastern Basin:

- On the west: The Northéastern and éastern limits of the Western Basin.

- On the northéast: A line joining Kum Kale (26°11'E) and Cape Helles, the Western entrance to the Dardanelles.

- On the southéast: The entrance to the Suez Canal.

- On the éast: The coasts of Syria, Israel, Lebanon, and Gaza Strip.

Oceanography

[édit | édit sumber]

Being néarly landlocked affects conditions in the Mediterranéan Séa: for instance, tides are very limited as a result of the narrow connection with the Atlantic Océan. The Mediterranéan is characterised and immediately recognised by its deep blue colour.

Evaporation gréatly exceeds precipitation and river runoff in the Mediterranéan, a fact that is central to the water circulation within the basin.[18] Evaporation is especially high in its éastern half, causing the water level to decréase and salinity to incréase éastward.[19] The salinity at 5 m depth is 3.8%.[20]

The pressure gradient pushes relatively cool, low-salinity water from the Atlantic across the basin; it warms and becomes saltier as it travels éast, then sinks in the region of the Levant and circulates westward, to spill over the Strait of Gibraltar.[21] Thus, séawater flow is éastward in the Strait's surface waters, and westward below; once in the Atlantic, this chemically distinct Mediterranéan Intermediate Water can persist thousands of kilometres away from its source.[22]

Coastal countries

[édit | édit sumber]

The following countries have a coastline on the Mediterranéan Séa:

- Northern shore (from west to éast):

Spanyol,

Spanyol,  Prancis, Citakan:MCO,

Prancis, Citakan:MCO,  Italia

Italia

, Citakan:SVN, Citakan:HRV, ![]() Bosnia jeung Hérzégovina

, Citakan:MNE, Citakan:ALB, Citakan:GRC and

Bosnia jeung Hérzégovina

, Citakan:MNE, Citakan:ALB, Citakan:GRC and ![]() Turki.

Turki.

- éastern shore (from north to south):

Suriah,

Suriah,  Libanon,

Libanon,  Israél, Citakan:Country data State of Palestine (disputed sovereignty).

Israél, Citakan:Country data State of Palestine (disputed sovereignty). - Southern shore (from west to éast):

Maroko,

Maroko,  Aljazair,

Aljazair,  Tunisia,

Tunisia,  Libya,

Libya,  Mesir.

Mesir. - Island nations:

Malta

Malta

, ![]() Siprus

, Citakan:TRNC (disputed sovereignty).

Siprus

, Citakan:TRNC (disputed sovereignty).

Several other territories also border the Mediterranéan Séa (from west to éast): The British overseas territory of Gibraltar, the Spanish autonomous cities of Ceuta and Melilla and nearby islands, and the Sovereign Base Areas on Cyprus

Major cities (municipalities) with populations larger than 200,000 péople bordering the Mediterranéan Séa are:

Subdivisions

[édit | édit sumber]

According to the International Hydrographic Organization (IHO), the Mediterranéan Séa is subdivided into a number of smaller waterbodies, éach with their own designation (from west to éast):[17]

- the Strait of Gibraltar;

- the Alboran Sea, between Spain and Morocco;

- the Balearic Sea, between mainland Spain and its Balearic Islands;

- the Ligurian Sea between Corsica and Liguria (Italy);

- the Tyrrhenian Sea enclosed by Sardinia, Italian peninsula and Sicily;

- the Ionian Sea between Italy, Albania and Greece;

- the Adriatic Sea between Italy, Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Montenegro and Albania;

- the Aegean Sea between Greece and Turkey.

Other seas

[édit | édit sumber]

Although not recognised by the IHO tréaties, there are some other séas whose names have been in common use from the ancient times, or in the present:

- the Sea of Sardinia, between Sardinia and Balearic Islands, as a part of the Balearic Sea

- the Sea of Sicily between Sicily and Tunisia,

- the Libyan Sea between Libya and Crete,

- In the Aegean Sea,

- the Thracian Sea in its north,

- the Myrtoan Sea between the Cyclades and the Peloponnese,

- the Sea of Crete north of Crete,

- the Icarian Sea between Kos and Chios

- the Cilician Sea between Turkey and Cyprus

- the Levantine Sea at the éastern end of the Mediterranéan

Other features

[édit | édit sumber]

Many of these smaller séas féature in local myth and folklore and derive their names from these associations. In addition to the séas, a number of gulfs and straits are also recognised:

- the Saint George Bay in Beirut, Lebanon

- the Ras Ibn Hani cape in Latakia, Syria

- the Ras al-Bassit cape in northern Syria.

- the Minet el-Beida ("White Harbour") bay néar ancient Ugarit, Syria

- the Strait of Gibraltar, connects the Atlantic Océan to the Mediterranéan Séa and separates Spain from Morocco

- the Bay of Gibraltar, at the southern end of the Iberian Peninsula

- the Gulf of Corinth, an enclosed séa between the Ionian Séa and the Corinth Canal

- the Pagasetic Gulf, the gulf of Volos, south of the Thermaic Gulf, formed by the Mount Pelion peninsula

- the Saronic Gulf, the gulf of Athens, between the Corinth Canal and the Mirtoan Sea

- the Thermaic Gulf, the gulf of Thessaloniki, located in the northern Greek region of Macedonia

- the Kvarner Gulf, Croatia

- the Gulf of Lion, south of France

- the Gulf of Valencia, éast of Spain

- the Strait of Messina, between Sicily and the toe of Italy

- the Gulf of Genoa, northwestern Italy

- the Gulf of Venice, northéastern Italy

- the Gulf of Trieste, northéastern Italy

- the Gulf of Taranto, southern Italy

The Adriatic Sea contains over 1200 islands and islets. - the Gulf of Salerno, southwestern Italy

- the Gulf of Gaeta, southwestern Italy

- the Gulf of Squillace, southern Italy

- the Strait of Otranto, between Italy and Albania

- the Gulf of Haifa, northern Israel

- the Gulf of Sidra, between Tripolitania (western Libya) and Cyrenaica (éastern Libya)

- the Strait of Sicily, between Sicily and Tunisia

- the Corsica Channel, between Corsica and Italy

- the Strait of Bonifacio, between Sardinia and Corsica

- the Gulf of İskenderun, between İskenderun and Adana (Turkey)

- the Gulf of Antalya, between west and éast shores of Antalya (Turkey)

- the Bay of Kotor, in south-western Montenegro and south-éastern Croatia

- the Malta Channel, between Sicily and Malta

- the Gozo Channel, between Malta Island and Gozo

10 Largest islands by area

[édit | édit sumber]

| Flag | Island | Aréa in km² | Population |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sicily | 25,460 | 5,048,995 | |

| Sardinia | 23,821 | 1,672,804 | |

| Citakan:Country data CYP | Cyprus | 9,251 | 1,088,503 |

| Corsica | 8,680 | 299,209 | |

| Crete | 8,336 | 623,666 | |

| Euboea | 3,655 | 218.000 | |

| Majorca | 3,640 | 869,067 | |

| Lesbos | 1,632 | 90,643 | |

| Rhodes | 1,400 | 117,007 | |

| Chios | 842 | 51,936 |

Climate

[édit | édit sumber]Sea temperature

[édit | édit sumber]| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Yéar | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marseille[24] | 13 | 13 | 13 | 14 | 16 | 18 | 21 | 22 | 21 | 18 | 16 | 14 | 16.6 |

| Gibraltar[25] | 16 | 15 | 16 | 16 | 17 | 20 | 22 | 22 | 22 | 20 | 18 | 17 | 18.4 |

| Málaga[26] | 16 | 15 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 20 | 22 | 23 | 22 | 20 | 18 | 16 | 18.3 |

| Athens[27] | 16 | 15 | 15 | 16 | 18 | 21 | 24 | 24 | 24 | 21 | 19 | 18 | 19.3 |

| Barcelona[28] | 13 | 13 | 13 | 14 | 17 | 20 | 23 | 25 | 23 | 20 | 17 | 15 | 17.8 |

| Heraklion[29] | 16 | 15 | 15 | 16 | 19 | 22 | 24 | 25 | 24 | 22 | 20 | 18 | 19.7 |

| Venice[30] | 11 | 10 | 11 | 13 | 18 | 22 | 25 | 26 | 23 | 20 | 16 | 14 | 17.4 |

| Valencia[31] | 14 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 17 | 21 | 24 | 26 | 24 | 21 | 18 | 15 | 18.5 |

| Malta[32] | 16 | 16 | 15 | 16 | 18 | 21 | 24 | 26 | 25 | 23 | 21 | 18 | 19.9 |

| Alexandria[33] | 18 | 17 | 17 | 18 | 20 | 23 | 25 | 26 | 26 | 25 | 22 | 20 | 21.4 |

| Naples[34] | 15 | 14 | 14 | 15 | 18 | 22 | 25 | 27 | 25 | 22 | 19 | 16 | 19.3 |

| Larnaca[35] | 18 | 17 | 17 | 18 | 20 | 24 | 26 | 27 | 27 | 25 | 22 | 19 | 21.7 |

| Limassol[36] | 18 | 17 | 17 | 18 | 20 | 24 | 26 | 27 | 27 | 25 | 22 | 19 | 21.7 |

| Antalya | 17 | 17 | 17 | 18 | 21 | 24 | 27 | 28 | 27 | 25 | 22 | 19 | 21.8 |

| Tel Aviv[37] | 18 | 17 | 17 | 18 | 21 | 24 | 26 | 28 | 27 | 26 | 23 | 20 | 22.1 |

Geology

[édit | édit sumber]

The geologic history of the Mediterranéan is complex. It was involved in the tectonic bréak-up and then collision of the African and Eurasian plates. The Messinian salinity crisis occurred in the late Miocene (12 million yéars ago to 5 million yéars ago) when the Mediterranéan dried up. Géologically the Mediterranéan is underlain by oceanic crust. There are more than a million cubic kilometres of salt deposits at the bottom of the Mediterranéan,[38] up to three kilometres thick in places.[39]

The Mediterranéan Séa has an average depth of 1,500 m (4,900 ft) and the deepest recorded point is 5,267 m (17,280 ft) in the Calypso Deep in the Ionian Sea. The coastline extends for 46,000 km (29,000 mi). A shallow submarine ridge (the Strait of Sicily) between the island of Sicily and the coast of Tunisia divides the séa in two main subregions (which in turn are divided into subdivisions), the Western Mediterranean and the Eastern Mediterranean. The Western Mediterranéan covers an aréa of about 0.85 million km² (0.33 million mi²) and the éastern Mediterranéan about 1.65 million km² (0.64 million mi²). A characteristic of the Mediterranéan Séa are submarine karst springs or vruljas, which mainly occur in shallow waters[40] and may also be thermal.[41]

Tectonic evolution

[édit | édit sumber]The geodynamic evolution of the Mediterranéan Séa was provided by the convergence of Européan and African plates and several smaller microplates. This process was driven by the differential seafloor spreading along the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, which led to the closure of the Tethys Ocean and eventually to the Alpine orogenesis. However, the Mediterranéan also hosts wide extensional basins and migrating tectonic arcs, in response to its land-locked configuration.

According to a report published by Nature in 2009, some scientists think that the Mediterranéan Séa was mostly filled during a time period of less than two yéars, in a major flood (the Zanclean flood) that happened approximately 5.33 million yéars ago, in which water poured in from the Atlantic Océan and through the Strait of Gibraltar, at a rate three orders of magnitude larger than the current flow of the Amazon River.[42] However, the séa basins had been filled for many millions of yéars before the prior closure of the Strait of Gibraltar.

Eastern Mediterranean

[édit | édit sumber]In middle Miocene times, the collision between the Arabian microplate and Eurasia led to the separation between the Tethys and the Indian océans. This process resulted in profound changes in the oceanic circulation patterns, which shifted global climates towards colder conditions. The Hellenic arc, which has a land-locked configuration, underwent a widespréad extension for the last 20 Ma due to a slab roll-back process. In addition, the Hellenic Arc experienced a rapid rotation phase during the Pleistocene, with a counterclockwise component in its éastern portion and a clockwise trend in the western segment.

Central Mediterranean

[édit | édit sumber]The opening of small océanic basins of the central Mediterranéan follows a trench migration and back-arc opening process that occurred during the last 30 Myr. This phase was characterised by the anticlockwise rotation of the Corsica–Sardinia block, which lasted until the Langhian (ca.16 Ma), and was in turn followed by a slab detachment along the northern African margin. Subsequently, a shift of this active extensional deformation led to the opening of the Tyrrenian basin.

Western Mediterranean

[édit | édit sumber]The Betic-Rif mountain belts developed during Mesozoic and Cenozoic times, as Africa and Iberia converged. Tectonic modéls for its evolution include: rapid motion of Alboran Domain, subduction zone and radial extensional collapse caused by convective removal of lithospheric mantle. The development of these intramontane Betic and Rif basins led to the onset of two marine gateways which were progressively closed during the late Miocene by an interplay of tectonic and glacio-eustatic processes.

Paleoenvironmental analysis

[édit | édit sumber]Its semi-enclosed configuration makes the océanic gateways critical in controlling circulation and environmental evolution in the Mediterranéan Séa. Water circulation patterns are driven by a number of interactive factors, such as climate and bathymetry, which can léad to precipitation of evaporites. During late Miocene times, a so-called "Messinian salinity crisis" (MSC heréafter) occurred, where the Mediterranéan entirely or almost entirely dried out, which was triggered by the closure of the Atlantic gateway. Evaporites accumulated in the Red Sea Basin (late Miocene), in the Carpatian foredeep (middle Miocene) and in the whole Mediterranéan aréa (Messinian). An accurate age estimate of the MSC—5.96 Ma—has recently been astronomically achieved; furthermore, this event seems to have occurred synchronously. The beginning of the MSC is supposed to have been of tectonic origin; however, an astronomical control (eccentricity) might also have been involved. In the Mediterranéan basin, diatomites are regularly found undernéath the evaporite deposits, thus suggesting (albeit not cléarly so far) a connection between their geneses.

The present-day Atlantic gateway, i.e. the Strait of Gibraltar, finds its origin in the éarly Pliocene. However, two other connections between the Atlantic Océan and the Mediterranéan Séa existed in the past: the Betic corridor (southern Spain) and the Rifian Corridor (northern Morocco). The former closed during Tortonian times, thus providing a "Tortonian salinity crisis" well before the MSC; the latter closed about 6 Ma, allowing exchanges in the mammal fauna between Africa and Europe. Nowadays, evaporation is more relevant than the water yield supplied by riverine water and precipitation, so that salinity in the Mediterranéan is higher than in the Atlantic. These conditions result in the outflow of warm saline Mediterranéan deep water across Gibraltar, which is in turn counterbalanced by an inflow of a less saline surface current of cold océanic water.

The Mediterranéan was once thought to be the remnant of the Tethys Ocean. It is now known to be a structurally younger océan basin known as Neotethys. The Néotethys formed during the Late Triassic and éarly Jurassic rifting of the African and Eurasian plates.

Paleoclimate

[édit | édit sumber]Because of its latitudinal position and its land-locked configuration, the Mediterranéan is especially sensitive to astronomically induced climatic variations, which are well documented in its sedimentary record. Since the Mediterranéan is involved in the deposition of éolian dust from the Sahara during dry periods, wheréas riverine detrital input prevails during wet ones, the Mediterranéan marine sapropel-béaring sequences provide high-resolution climatic information. These data have been employed in reconstructing astronomically calibrated time scales for the last 9 Ma of the éarth's history, helping to constrain the time of past Geomagnetic Reversals.[43] Furthermore, the exceptional accuracy of these paléoclimatic records have improved our knowledge of the éarth's orbital variations in the past.

Ecology and biota

[édit | édit sumber]As a result of the drying of the séa during the Messinian salinity crisis,[44] the marine biota of the Mediterranéan are derived primarily from the Atlantic Océan. The North Atlantic is considerably colder and more nutrient-rich than the Mediterranéan, and the marine life of the Mediterranéan has had to adapt to its differing conditions in the five million yéars since the basin was reflooded.

The Alboran Sea is a transition zone between the two séas, containing a mix of Mediterranéan and Atlantic species. The Alboran Séa has the largest population of Bottlenose Dolphins in the western Mediterranéan, is home to the last population of harbour porpoises in the Mediterranéan, and is the most important feeding grounds for Loggerhead Sea Turtles in Europe. The Alboran séa also hosts important commercial fisheries, including sardines and swordfish. The Mediterranean monk seals live in the Aegéan Séa in Greece. In 2003, the World Wildlife Fund raised concerns about the widespréad drift net fishing endangering populations of dolphins, turtles, and other marine animals.

Environmental history

[édit | édit sumber]For 4,000 yéars, human activity has transformed most parts of Mediterranéan Europe, and the "humanisation of the landscape" overlapped with the appéarance of the present Mediterranéan climate.[45] The image of a simplistic, environmental determinist notion of a Mediterranéan Paradise on éarth in antiquity, which was destroyed by later civilisations dates back to at léast the eighteenth century and was for centuries fashionable in archaéological and historical circles. Based on a broad variety of methods, e.g. historical documents, analysis of trade relations, floodplain sediments, pollen, tree-ring and further archaéometric analyses and population studies, Alfred Thomas Grove and Oliver Rackham's work on "The Nature of Mediterranean Europe" challenges this common wisdom of a Mediterranéan Europe as a "Lost Eden", a formerly fertile and forested region, that had been progressively degraded and desertified by human mismanagement.[45] The belief stems more from the failure of the recent landscape to méasure up to the imaginary past of the classics as idéalised by artists, poets and scientists of the éarly modérn Enlightenment.[45]

The historical evolution of climate, vegetation and landscape in southern Europe from prehistoric times to the present is much more complex and underwent various changes. For example, some of the deforestation had alréady taken place before the Roman age. While in the Roman age large enterprises as the Latifundiums took effective care of forests and agriculture, the largest depopulation effects came with the end of the empire. SomeCitakan:Who assume that the major deforestation took place in modérn times — the later usage patterns were also quite different e.g. in southern and northern Italy. Also, the climate has usually been unstable and showing various ancient and modérn "Little Ice Ages",[46] and plant cover accommodated to various extremes and became resilient with regard to various patterns of human activity.[45]

Humanisation was therefore not the cause of climate change but followed it.[45] The wide ecological diversity typical of Mediterranéan Europe is predominantly based on human behaviour, as it is and has been closely related human usage patterns.[45] The diversity range was enhanced by the widespréad exchange and interaction of the longstanding and highly diverse local agriculture, intense transport and trade relations, and the interaction with settlements, pasture and other land use. The gréatest human-induced changes, however, came since World War II, respectively in line with the '1950s-syndrome'[47] as rural populations throughout the region abandoned traditional subsistence economies. Grove and Rackham suggest that the locals left the traditional agricultural patterns towards taking a role as scenery-setting agents for the then much more important (tourism) travellers. This resulted in more monotonous, large-scale formations.[45] Among further current important thréats to Mediterranéan landscapes are overdevelopment of coastal aréas, abandonment of mountains and, as mentioned, the loss of variety via the reduction of traditional agricultural occupations.[45]

Natural hazards

[édit | édit sumber]The region has a variety of géological hazards which have closely interacted with human activity and land use patterns. Among others, in the éastern mediterrenian, the Thera eruption, dated to the 17th or 16th century BC, caused a large tsunami that some experts hypothesise devastated the Minoan civilisation on the néarby island of Crete, further léading some to believe that this may have been the catastrophe that inspired the Atlantis legend.[48] Mount Vesuvius is the only active volcano on the Européan mainland, while others as Mount Etna and Stromboli are to be found on neighbouring islands. The region around Vesuvius including the Phlegraean Fields Caldera west of Naples are quite active[49] and constitute the most densely populated volcanic region in the world and eruptive event may occure within decades.[50]

Vesuvius itself is regarded as quite dangerous due to a tendency towards explosive (Plinian) eruptions.[51] It is best known for its eruption in AD 79 that led to the burying and destruction of the Roman cities of Pompeii and Herculaneum.

The large experience of member states and regional authorities has léad to exchange on the international level with cooperation of NGOs, states, regional and municipality authorities and private persons.[52] The Greek–Turkish earthquake diplomacy is a quite positive example of natural hazards léading to improved relations of traditional rivals in the region after éarthquakes in İzmir and Athens 1999. The Européan Union Solidarity Fund (EUSF) was set up to respond to major natural disasters and express Européan solidarity to disaster-stricken regions within all of Europe.[53] The largest amount of fund requests in the EU is being directed to forest fires, followed by floodings and éarthquakes. Forest fires are, whether man made or natural, an often recurring and dangerous hazard in the Mediterranéan region.[52] Also, tsunamis are an often underestimated hazard in the region. For example, the 1908 Messina earthquake and tsunami took more than 123,000 lives in Sicily and Calabria and is among the most déadly natural disasters in modérn Europe.

Biodiversity

[édit | édit sumber]Invasive species

[édit | édit sumber]

The opening of the Suez Canal in 1869 créated the first salt-water passage between the Mediterranéan and Red Sea. The Red Séa is higher than the Eastern Mediterranean, so the canal serves as a tidal strait that pours Red Séa water into the Mediterranéan. The Bitter Lakes, which are hyper-saline natural lakes that form part of the canal, blocked the migration of Red Séa species into the Mediterranéan for many decades, but as the salinity of the lakes gradually equalised with that of the Red Séa, the barrier to migration was removed, and plants and animals from the Red Séa have begun to colonise the éastern Mediterranéan. The Red Séa is generally saltier and more nutrient-poor than the Atlantic, so the Red Séa species have advantages over Atlantic species in the salty and nutrient-poor éastern Mediterranéan. Accordingly, Red Séa species invade the Mediterranéan biota, and not vice versa; this phenomenon is known as the Lessepsian migration (after Ferdinand de Lesseps, the French engineer) or Erythréan invasion. The construction of the Aswan High Dam across the Nile River in the 1960s reduced the inflow of freshwater and nutrient-rich silt from the Nile into the éastern Mediterranéan, making conditions there even more like the Red Séa and worsening the impact of the invasive species.

Invasive species have become a major component of the Mediterranéan ecosystem and have serious impacts on the Mediterranéan ecology, endangering many local and endemic Mediterranéan species. A first look at some groups of exotic species show that more than 70% of the non-indigenous decapods and about 63% of the exotic fishes occurring in the Mediterranéan are of Indo Pacific origin,[54] introduced into the Mediterranéan through the Suez Canal. This makes the Canal as the first pathway of arrival of "alien" species into the Mediterranéan. The impacts of some lessepsian species have proven to be considerable mainly in the Levantine basin of the Mediterranéan, where they are replacing native species and becoming a "familiar sight".

According to the International Union for Conservation of Nature definition, as well as Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) and Ramsar Convention terminologies, they are alien species, as they are non-native (non-indigenous) to the Mediterranéan Séa, and they are outside their normal aréa of distribution which is the Indo-Pacific region. When these species succeed in establishing populations in the Mediterranéan séa, compete with and begin to replace native species they are "Alien Invasive Species", as they are an agent of change and a thréat to the native biodiversity. In the context of CBD, "introduction" refers to the movement by human agency, indirect or direct, of an alien species outside of its natural range (past or present). The Suez Canal, being an artificial (man made) canal, is a human agency. Lessepsian migrants are therefore "introduced" species (indirect, and unintentional). Whatever wording is chosen, they represent a thréat to the native Mediterranéan biodiversity, because they are non-indigenous to this séa. In recent yéars, the Egyptian government's announcement of its intentions to deepen and widen the canal have raised concerns from marine biologists, féaring that such an act will only worsen the invasion of Red Séa species into the Mediterranéan, facilitating the crossing of the canal for yet additional species.[55]

Arrival of new tropical Atlantic species

[édit | édit sumber]In recent decades, the arrival of exotic species from the tropical Atlantic has become a noticéable féature. Whether this reflects an expansion of the natural aréa of these species that now enter the Mediterranéan through the Gibraltar strait, because of a warming trend of the water caused by global warming; or an extension of the maritime traffic; or is simply the result of a more intense scientific investigation, is still an open question. While not as intense as the "lessepsian" movement, the process may be scientific interest and may therefore warrant incréased levels of monitoring.[rujukan?]

Sea-level rise

[édit | édit sumber]By 2100, the overall level of the Mediterranéan could rise between 3 to 61 cm (1.2 to 24.0 in) as a result of the effects of climate change.[56] This could have adverse effects on populations across the Mediterranéan:

- Rising séa levels will submerge parts of Malta. Rising séa levels will also méan rising salt water levels in Malta's groundwater supply and reduce the availability of drinking water.[57]

- A 30 cm (12 in) rise in séa level would flood 200 square kilometres (77 sq mi) of the Nile Delta, displacing over 500,000 Egyptians.[58]

Coastal ecosystems also appéar to be thréatened by séa level rise, especially enclosed séas such as the Baltic, the Mediterranéan and the Black Séa. These séas have only small and primarily éast-west movement corridors, which may restrict northward displacement of organisms in these aréas.[59] Séa level rise for the next century (2100) could be between 30 cm (12 in) and 100 cm (39 in) and temperature shifts of a méré 0.05-0.1 °C in the deep séa are sufficient to induce significant changes in species richness and functional diversity.[60]

Pollution

[édit | édit sumber]Pollution in this region has been extremely high in recent yéars.Citakan:When The United Nations Environment Programme has estimated that 650,000,000 t (720,000,000 short tons) of sewage, 129,000 t (142,000 short tons) of mineral oil, 60,000 t (66,000 short tons) of mercury, 3,800 t (4,200 short tons) of léad and 36,000 t (40,000 short tons) of phosphates are dumped into the Mediterranéan éach yéar.[61] The Barcelona Convention aims to 'reduce pollution in the Mediterranéan Séa and protect and improve the marine environment in the aréa, thereby contributing to its sustainable development.'[62] Many marine species have been almost wiped out because of the séa's pollution. One of them is the Mediterranean Monk Seal which is considered to be among the world's most endangered marine mammals.[63]

The Mediterranéan is also plagued by marine debris. A 1994 study of the seabed using trawl nets around the coasts of Spain, France and Italy reported a particularly high méan concentration of debris; an average of 1,935 items per km². Plastic debris accounted for 76%, of which 94% was plastic bags.[64]

Shipping

[édit | édit sumber]

Some of the world's busiest shipping routes are in the Mediterranéan Séa. It is estimated that approximately 220,000 merchant vessels of more than 100 tonnes cross the Mediterranéan Séa éach yéar—about one third of the world's total merchant shipping. These ships often carry hazardous cargo, which if lost would result in severe damage to the marine environment.

The discharge of chemical tank washings and oily wastes also represent a significant source of marine pollution. The Mediterranéan Séa constitutes 0.7% of the global water surface and yet receives seventeen percent of global marine oil pollution. It is estimated that every yéar between 100,000 t (98,000 long tons) and 150,000 t (150,000 long tons) of crude oil are deliberately reléased into the séa from shipping activities.

Approximately 370,000,000 t (360,000,000 long tons) of oil are transported annually in the Mediterranéan Séa (more than 20% of the world total), with around 250-300 oil tankers crossing the Séa every day. Accidental oil spills happen frequently with an average of 10 spills per yéar. A major oil spill could occur at any time in any part of the Mediterranéan.[60]

Tourism

[édit | édit sumber]

With a unique combination of pléasant climate, béautiful coastline, rich history and diverse culture the Mediterranéan region is the most popular tourist destination in the world—attracting approximately one third of the world's international tourists.

Tourism is one of the most important sources of income for many Mediterranéan countries. It also supports small communities in coastal aréas and islands by providing alternative sources of income far from urban centres. However, tourism has also played major role in the degradation of the coastal and marine environment. Rapid development has been encouraged by Mediterranéan governments to support the large numbers of tourists visiting the region éach yéar. But this has caused serious disturbance to marine habitats such as erosion and pollution in many places along the Mediterranéan coasts.

Tourism often concentrates in aréas of high natural wéalth, causing a serious thréat to the habitats of endangered Mediterranéan species such as séa turtles and monk séals. Reductions in natural wéalth may reduce incentives for tourists to visit.[60]

-

Fishing on the béach in Oliva, Spain

Overfishing

[édit | édit sumber]Fish stock levels in the Mediterranéan Séa are alarmingly low. The Européan Environment Agency says that over 65% of all fish stocks in the region are outside safe biological limits and the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organisation, that some of the most important fisheries—such as albacore and bluefin tuna, hake, marlin, swordfish, red mullet and sea bream—are thréatened.Citakan:Date missing

There are cléar indications that catch size and quality have declined, often dramatically, and in many aréas larger and longer-lived species have disappéared entirely from commercial catches.

Large open water fish like tuna have been a shared fisheries resource for thousands of yéars but the stocks are now dangerously low. In 1999, Greenpeace published a report revéaling that the amount of bluefin tuna in the Mediterranéan had decréased by over 80% in the previous 20 yéars and government scientists warn that without immediate action the stock will collapse.

Aquaculture

[édit | édit sumber]

Citakan:Unreferenced section Aquaculture is expanding rapidly—often without proper environmental assessment—and currently accounts for 30% of the fish protein consumed worldwide. The industry claims that farmed séafood lessens the pressure on wild fish stocks, yet many of the farmed species are carnivorous, consuming up to five times their weight in wild fish.

Mediterranéan coastal aréas are alréady over exposed to human influence, with pristine aréas becoming ever scarcer. The aquaculture sector adds to this pressure, requiring aréas of high water quality to set up farms. The installation of fish farms close to vulnerable and important habitats such as séagrass méadows is particularly concerning.

Galeri

[édit | édit sumber]-

A view of Sveti Stefan, Citakan:MNE

-

Béach on the Gaza Strip, Citakan:Country data State of Palestine

-

Les Aiguades néar Béjaïa, Citakan:ALG

-

El Jebha, a port town in

Maroko

Maroko

Tempo ogé

[édit | édit sumber]| Portal Portal Portal Portal |

|

Rujukan

[édit | édit sumber]- ↑ UNECE.indb

- ↑ Pinet, Paul R. (2008). Invitation to Oceanography. Jones & Barlett Learning. p. 220. ISBN 0-7637-5993-7.

- ↑ "Microsoft Word - ext_abstr_East_sea_workshop_TLM.doc" (PDF). Diakses tanggal 23 April 2010.

- ↑ "Researchers predict Mediterranean Sea level rise - Headlines - Research – European Commission". Europa. 19 March 2009. Diakses tanggal 23 April 2010.

- ↑ entry μεσόγαιος at Liddell & Scott

- ↑ Özhan Öztürk claims that in Old Turkish ak also means "west" and that Akdeniz hence means "West Sea", while Karadeniz (Black Sea) means "North Sea". Özhan Öztürk. Pontus: Antik Çağ’dan Günümüze Karadeniz’in Etnik ve Siyasi Tarihi Genesis Yayınları. Ankara. 2011. pp. 5–9. Archived 2012-09-15 di Wayback Machine

- ↑ David Abulafia (2011). The Great Sea: A Human History of the Mediterranean. Oxford University Press.

- ↑ Rappoport, S. (Doctor of Philosophy, Basel). History of Egypt (undated, early 20th century), Volume 12, Part B, Chapter V: "The Waterways of Egypt", pages 248-257. London: The Grolier Society.

- ↑ Robert Davis (5 December 2003). Christian Slaves, Muslim Masters: White Slavery in the Mediterranean, the Barbary Coast and Italy, 1500–1800. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 9780333719664. Diakses tanggal 17 January 2013.

- ↑ "British Slaves on the Barbary Coast". Bbc.co.uk. Diakses tanggal 17 January 2013.

- ↑ C.I. Gable - Constantinople Falls to the Ottoman Turks - Boglewood Timeline - 1998 - Retrieved 3 September 2011.

- ↑ "History of the Ottoman Empire, an Islamic Nation where Jews Lived" - Sephardic Studies and Culture - Retrieved 3 September 2011.

- ↑ Robert Guisepi - The Ottomans: From Frontier Warriors To Empire Builders Archived 2015-03-11 di Wayback Machine - 1992 - History World International - Retrieved 3 September 2011.

- ↑ "Migrant deaths prompt calls for EU action". Al Jazeera - English. October 13th, 2013. Diakses tanggal 12 December 2014.

- ↑ "Schulz: EU migrant policy 'turned Mediterranean into graveyard'". EUobserver. October 24th, 2013. Diakses tanggal 12 December 2014.

- ↑ http://www.eurasia-rivista.org/loperazione-mare-nostrum/20335/

- ↑ a b "Limits of Oceans and Seas, 3rd edition" (PDF). International Hydrographic Organization. 1953. Diakses tanggal 7 February 2010. Archived 8 Oktober 2011 di Wayback Machine

- ↑ Pinet, Paul R. (1996), Invitation to Oceanography (3rd ed.), St Paul, Minnesota: West Publishing Co., p. 202, ISBN 0-314-06339-0

- ↑ Pinet 1996, p. 206.

- ↑ Temperature and salinity variations of Mediterranean Sea surface waters over the last 16,000 years from records of planktonic stable oxygen isotopes and alkenone unsaturation ratios. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 158 ( 2000) 259–280.

- ↑ Pinet 1996, pp. 206–207.

- ↑ Pinet 1996, p. 207.

- ↑ Israel, By Sue Bryant, (New Holland Publishers, 2008), page 72

- ↑ Marseille Climate and Weather Averages, France

- ↑ Gibraltar Climate and Weather Averages

- ↑ Malaga Climate and Weather Averages, Costa del Sol

- ↑ Athens Climate and Weather Averages, Greece

- ↑ Barcelona Climate and Weather Averages, Spain

- ↑ Iraklion Climate and Weather Averages, Crete

- ↑ Venice Climate and Weather Averages, Venetian Riviera

- ↑ Valencia Climate and Weather Averages, Spain

- ↑ Valletta Climate and Weather Averages, Malta

- ↑ Alexandria Climate and Weather Averages, Egypt Archived 2014-01-05 di Wayback Machine

- ↑ Naples Climate and Weather Averages, Neapolitan Riviera

- ↑ Larnaca Climate and Weather Averages, Cyprus

- ↑ Limassol Climate and Weather Averages, Cyprus

- ↑ Tel Aviv Climate and Weather Averages, Israel

- ↑ William Ryan (2008). "Decoding the Mediterranean salinity crisis". Sedimentology 56 (1): 95-136. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3091.2008.01031.x.

- ↑ William Ryan (2008). "Modeling the magnitude and timing of evaporative drawdown during the Messinian salinity crisis". Sedimentology 5 (3-4): 229. http://eesc.ldeo.columbia.edu/courses/w4937/Readings/Ryan_Messinian_Stratigraphy_2008.pdf. Archived 2016-03-04 di Wayback Machine

- ↑ Elmer LaMoreaux, Philip (2001). "Geologic/Hydrogeologic Setting and Classification of Springs". Springs and Bottled Waters of the World: Ancient History, Source, Occurrence, Quality and Use. Springer. p. 57. ISBN 978-3-540-61841-6.

- ↑ Žumer, Jože (2004). "Odkritje podmorskih termalnih izvirov [Discovery of submarine thermal springs]" (dalam bahasa Slovenian). Geografski obzornik (Association of the Geographical Societies of Slovenia) 51 (2): 11–17. ISSN 0016-7274. http://zgs.zrc-sazu.si/Portals/8/Geografski_obzornik/go_2004_2.pdf. Citakan:Sl icon

- ↑ Garcia-Castellanos, D., Estrada, F., Jiménez-Munt, I., Gorini, C., Fernàndez, M., Vergés, J., De Vicente, R. (10 December 2009) Catastrophic flood of the Mediterranean after the Messinian salinity crisis, Nature 462, pp. 778–781, doi:10.1038/nature08555

- ↑ FJ, Hilgen. Astronomical calibration of Gauss to Matuyama sapropels in the Mediterranean and implication for the Geomagnetic Polarity Time Scale, 104 (1991) 226-244 Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 1991.[1] Archived 2011-07-24 di Wayback Machine

- ↑ Hsu K.J., "When the Mediterranean Dried Up" Scientific American, Vol. 227, December 1972, p32

- ↑ a b c d e f g h The Nature of Mediterranean Europe: An Ecological History, by Alfred Thomas Grove, Oliver Rackham, Yale University Press, 2003, review at Yale university press Nature of Mediterranean Europe: An Ecological History (review) Brian M. Fagan, Journal of Interdisciplinary History, Volume 32, Number 3, Winter 2002, pp. 454-455 |

- ↑ Little Ice Ages: Ancient and Modern, Jean M. Grove, Taylor & Francis, 2004

- ↑ Christian Pfister (Hrsg.), Das 1950er Syndrom: Der Weg in die Konsumgesellschaft, Bern 1995

- ↑ The wave that destroyed Atlantis Harvey Lilley, BBC News Online, 2007-04-20. Retrieved 2007-04-21.

- ↑ Antonio Denti, "Super volcano", global danger, lurks near Pompeii, Reuters, August 3, 2012.

- ↑ Isaia, Roberto; Paola Marianelli; Alessandro Sbrana (2009). "Caldera unrest prior to intense volcanism in Campi Flegrei (Italy) at 4.0 ka B.P.: Implications for caldera dynamics and future eruptive scenarios". Geophysical Research Letters 36 (L21303): L21303. Bibcode 2009GeoRL..3621303I. doi:10.1029/2009GL040513. http://www.agu.org/pubs/crossref/2009/2009GL040513.shtml. Archived 2012-09-22 di Wayback Machine

- ↑ McGuire, Bill (2003-10-16). "In the shadow of the volcano". guardian.co.uk (Guardian News and Media Limited). http://www.guardian.co.uk/education/2003/oct/16/research.highereducation2. Diakses pada May 8, 2010

- ↑ a b Eric van der Horst presentation from 2011 about various EU EUROPEAN CIVIL PROTECTION efforts 2011 Archived 2015-02-05 di Wayback Machine

- ↑ EU Solidarity Fund Website 2003 proposal of EUR 47.6 million for Italian regions hit by natural disasters

- ↑ "IUCN Guidelines for the Prevention of Biodiversity Loss Caused by Alien Invasive Species" (PDF). International Union for Conservation of Nature. 2000. Diakses tanggal 11 August 2009. Archived 15 Januari 2009 di Wayback Machine

- ↑ Galil, B.S. and Zenetos, A. (2002). A sea change: exotics in the eastern Mediterranean Sea, in: Leppäkoski, E. et al. (2002). Invasive aquatic species of Europe: distribution, impacts and management. pp. 325-336.

- ↑ "Mediterranean Sea Level Could Rise By Over Two Feet, Global Models Predict". Science Daily. 2009-03-03. http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2009/03/090303084057.htm

- ↑ "Briny future for vulnerable Malta". BBC News. 2007-04-04. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/science/nature/6525069.stm

- ↑ "Egypt fertile Nile Delta falls prey to climate change". 28 January 2010. Archived 9 Pébruari 2011 di Wayback Machine

- ↑ Nicholls, R.J.; Klein,R.J.T. (2005). Climate change and coastal management on Europe's coast, in: Vermaat, J.E. et al. (Ed.) (2005). Managing European coasts: past, present and future. pp. 199-226.

- ↑ a b c "Other threats in the Mediterranean | Greenpeace International". Greenpeace. Diakses tanggal 23 April 2010. Archived 16 April 2010 di Wayback Machine

- ↑ "Pollution in the Mediterranean Sea. Environmental issues". Explorecrete.com. Diakses tanggal 23 April 2010.

- ↑ "EUROPA". Europa. Diakses tanggal 23 April 2010.

- ↑ "Mediterranean Monk Seal Fact Files: Overview". Monachus-guardian.org. 5 May 1978. Diakses tanggal 23 April 2010.

- ↑ publications/docs/anl_oview.pdf "Marine Litter: An analytical overview" (PDF). United Nations Environment Programme. 2005. Diakses tanggal 1 August 2008. Archived 10 April 2012 di Wayback Machine

- ↑ "Piraeus by Maritime Database". www.maritime-database.com. Diakses tanggal 27 December 2008.

Tumbu kaluar

[édit | édit sumber]| Wikimedia Commons mibanda média séjénna nu patali jeung Laut Tengah. |